The problem with money may not be what you think: an alternative analysis of the root of the problem.

A guest editorial by Michel Foata-Prestavoine. The Problem is the Transactional Symmetry, and the proposed solution is the Common Good Unit, a commons-based monetary system.

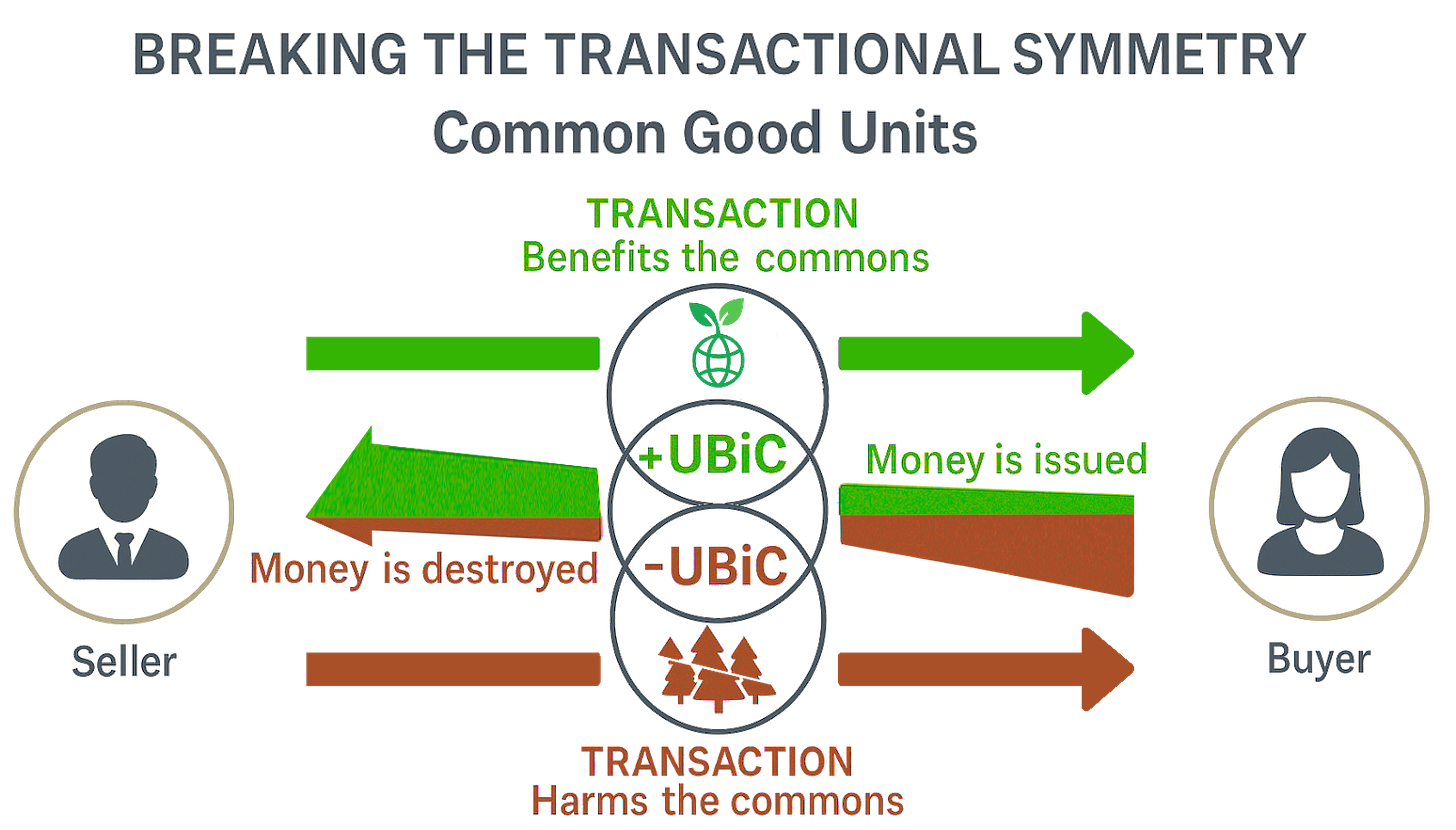

Theme of the guest article below: A proposal for the creation of UBiC, for French Unité de Bien Commun: a proposed currency that breaks the symmetry of exchanges and thereby materializes in money not only private interest but also the common interest.

But first:

Introduction by Michel Bauwens

Many people who look at social change, and for a magical formula to end the exploitation of the human by the human, end up believing that the very design of ‘money’ is the problem, and in particular, the existence of positive interest, what the Ancients called Usury, and was therefore forbidden by nearly all ethical religions of the Axial Age.

The reasoning is the following:

If you have to pay back more than you borrow, this can only have two effects:

The first effect concerns the more static traditional pre-capitalist societies: if interest is allowed, it will shift resources to those who lend, and impoverish those who borrow, which will eventually end up in slavery. This is why interest-based lending was considered so negatively, and all kinds of measures were decided by the Kings and Emperors to avoid it, i.e. Debt Jubilees, Usury restrictions, Clean Slate legislations, etc .. It was this, or alternatively, Conquest directed at the outside world, to get the necessary compensating resources. When the limits and costs of such conquests was reached, the Empire in question would decline and collapse.

The second solution is to create a growth-based economy. This is what Bernard Lietaer explains in his Mystery of Money. Once the Cathars and the ‘southern French civilization’ with its negative interest money, was defeated, the introduction of royal positive-interest money led to the crisis of more or less steady-state Feudalism in the 14th century, and by necessity, the shift to growth-based Capitalism.

The conclusion from this reasoning is that if we transform this logic of money, we could return to a steady-state economy that could function with social and ecological balance. I have to admit that I still find this a very compelling analysis of the monetary situation we find ourselves in.

But the article below by Michel Foata goes beyond this analysis.

His radical hypothesis is that the cause of our global ecological and social crisis, is deeper and can be traced back to the very invention of money in the Neolithic!

So please read this paragraph carefully:

Michel Foata-Prestavoine explains:

“What we wish to introduce here as a new element for reflection is that the origin of this implicit project of current monetary tools—to sacrifice common value for the benefit of private value—lies in a specific property of money: transaction symmetry.

This is a fundamental property of currencies, inherited from the Neolithic era because it was constrained by the materiality of the first monetary supports (shells, precious metals, banknotes): what goes into one pocket necessarily comes out of another’s pocket. This symmetry persists today in monetary systems that have nonetheless become overwhelmingly digital: in every monetary transaction, what is recorded as a positive for one actor involved must be recorded as a negative in another’s account, without the creation or destruction of units. As a consequence, everyone wants “their money’s worth.” Every monetary transaction is currently only an exchange of private value.

This structure imposes a mode of operation: economic actors must maximize the added value of their activity by minimizing the prices borne by the client, and consequently, the private monetary costs borne by the seller. Everything that is not charged to them (because it concerns common goods with no owner: the atmosphere, biodiversity, social cohesion) is therefore externalized. This is why, in a globalized competitive system within economies disembedded from social relations (Polanyi 1944), the most profitable activities—those able to stabilize their value chains, motivate money issuance, and feed public revenues—are systemically those that destroy shared resources the most.”

And this then, is the consequence:

“Transaction symmetry creates, with each transaction, a reality we call tautocracy. A regime in which the monetary and accounting system self-validates tautologically and imposes itself on everyone, including political and economic leaders, and banking institutions. It forces every other regime—democratic, autocratic, technocratic…—to proclaim wealth where it is possible to record added economic value, and preferably by reducing the costs dedicated to the care of common capital (consumption or degradation of common resources, which have no owner and are by definition free and of zero monetary value).

On a macroeconomic scale, this translates into the observation that indicators of ecological and social health are anti-correlated with the GDP indicator. The most documented correlation being that between carbon emissions and GDP. Tautocracy, therefore, refers to this accounting illusion: a world that is becoming genuinely poorer but appears to be getting richer in its monetary balance sheets. As long as transaction symmetry structures our exchanges, this illusion cannot be dispelled: the economy remains trapped in a framework where what counts in every economic interaction between agents is not what has value for everyone, but what has a price for some.”

Here then, is the full guest editorial by Michel Foata. It does not just contain a critical analysis of what is wrong with the current monetary system, but also offers a solution!

Guest article: Money: Black Magic, White Magic, A Chronicle

– by Michel Foata-Prestavoine

Today, profitability depends on destroying the Common Good for the production of private goods.

We refuse to blame “human nature,” which everyone readily acknowledges as “selfish” in “other people,” but never in themselves or their loved ones. We also refuse because, despite the unstoppable expansion of money-driven civilization, there still exist isolated communities without currency. They testify to how humanity functioned for millennia before our era: caring for the commons was the rule, and private property the exception.

Money is a “stigmergic” phenomenon: It works like the pheromone trails left by ants. Each transaction leaves a mark, and these marks, when aggregated, guide subsequent ones. This property has allowed modern human societies to complexify exchanges incredibly, propagate them on a gigantic scale, and thus efficiently generalize—without plan or conductor—the lethal exploitation of social and environmental commons.

So, if we accept that this supposed foolish and frenzied selfishness of humanity is but a collective myth, constructed by our disillusionment with the drift of our civilization—the civilization of money—what then is the fundamental cause of this difficulty for each individual to care for the common good?

We believe that behind an innocuous mechanism, performed in every transaction, lies the deep root of our ecological and social impasse. We believe this mechanism is inherited from Neolithic shells and other early material supports of value—a property that renders money blind to the common interest. It is the fact that the sum entering one pocket can only be the sum that left another: the price of the transaction.

Indeed, let’s examine closely what happens in each transaction. To what is the value of our commons sacrificed? The answer is simple and well-known: it is sacrificed to the necessity of minimizing the seller’s intermediate production costs, enabling them to stabilize their business model while offering a competitive price to the customer, who is themselves legitimately seeking to stabilize their budget. Minimizing production costs dedicated to caring for the commons is generally simple and effective because these, by definition, have no owner to defend their value. Thus, consuming or degrading natural resources and disrupting social balances are powerful levers for optimizing production economic models. So, the Common Good is generally sacrificed to the compromise between the private interests of the parties involved in the transaction. And this is because they must agree on a common key quantity during the exchange—one on which they have conflicting private interests: its price.

Everything thus stems from a conventional determinism we’ve learned to consider obvious: What one receives, another must disburse. This is the meaning of the famous reminder from our politicians: “money isn’t magic.” Nothing is created or extinguished within the exchange, and the common good must always have its payer. Result: in every transaction, the basic unit of our collective economic intelligence, we can only recover in money the private interest of the payers, never the common interest of the absent. And the fate of the world remains off the books. The value of its care, though obvious to everyone, remains a cost, a private sacrifice for the involved parties.

This logic made sense in the Neolithic. The commons weren’t threatened, and the economy remained inseparable from local social rules: you couldn’t let your neighbor die from work, and cutting down a tree was of no concern. But since the industrial revolution, the globalization of exchanges has gradually allowed the economy to escape this control, just as we began developing the technical means to exceed planetary boundaries. Since money can only recognize the value of private interest in each transaction, the dynamics of predation have been amplified at all scales. Thus, regardless of individual will, the collective intelligence of our competitive and globalized economies has become blind. All cooperation has turned into competition, and all care into an unbearable cost for the market.

Facing planetary limits, today’s currencies—whether banking or decentralized (cryptocurrencies)—have thus all become obsolete, transformed into pheromones of a global economic intelligence that preys upon what everyone now considers most precious: our social and environmental commons, threatened with extinction.

Everyone finds their culprits—banks, the French Treasury, consumers, capitalists, states, or Big Tech... But these are merely the “natural” products of monetary logic, not the other way around. As long as our currencies do not recognize, in each transaction, the common value as much as the private value, sobriety and care will remain, radically, during transactions, a loss and a sacrifice for those who consent to them—including for states, from whom we ultimately expect regulatory constraints or value redistribution, at the expense of the relative international competitiveness of their own economies and their public revenues...

But if money is a spell, can’t we, as good magicians, reverse it?

We are convinced that switching from black magic to white magic isn’t so complicated. If money realizes the project inscribed in its architecture, perhaps we just need to rewrite that project.

Citizens, public institutions, and also, we believe, some captains of industry already sense this necessity to change what constitutes value. We read it implicitly, for instance, in a column published in the Journal du Dimanche in June 2022 by the CEOs of EDF, Engie, and TotalEnergies. In it, they jointly called for an “immediate, collective, and massive” effort towards energy sobriety and affirmed that their scientific and financial collaboration towards sobriety goals “will be fully effective under the guidance of state services and with the help of local authorities, economic actors, and our fellow citizens.” Didn’t they thereby implicitly recognize that what holds the most value is shifting towards the conditions for social cohesion and resilience? Perhaps they, too, are ready for this magic trick: to retrieve the lost wand and make it trace different circles in the air.

This is the wager of ongoing research on the Common Good Unit (UBiC for French Unité de Bien Commun): a proposed currency that breaks the symmetry of exchanges and thereby materializes in money not only private interest but also the common interest.

How? Through a simple reversal of the transaction mechanism: When the subject of a transaction has been legitimately recognized, in the territories affected by its production, as caring for their social and environmental commons, money is created during the exchange to acknowledge this common value, so that the buyer doesn’t pay for it, but the seller earns it. Conversely, when the transaction degrades the commons, value disappears, and the buyer pays more than the seller receives. The single price of current transactions thus splits into two quantities representing the private interests of the involved parties—the amount paid and the amount received—whose sum is no longer zero but equal to the recognized collective value of the exchange. This materialization of common value aligns private interests with the common interest. Profit remains possible, but it can no longer grow at the expense of its externalities.

In such a system, evaluating an production activity’s care for the common good is entrusted to Observatories of the Common Good (OBiC for French Observatoires du Bien Commun), local bodies where citizens, researchers, economic actors, and administrators are paid to deliberate together on what, in their territory, deserves recognition as common wealth. These observatories do not create value: they reveal and legitimately measure it. They make visible what the economy ignores, giving a monetary translation to care, cooperation, and regeneration.

This idea is not utopian: it aligns with the principles of liberalism itself.

The entrepreneur remains free to set their sales revenue; simply, a monetary bonus-malus, determined through a rigorous and legitimate process across all concerned territories, changes the price paid by the buyer. What changes is the signal of what is attractive and profitable. Bankers can continue to lend, investors to bet, customers to seek the least costly product, but the economy that heals the world becomes the most prosperous.

Initial simulations conducted using the serious game “The Adventurers of the Common Good” show that with such a currency, the correlation between economic value and the impact of our activities reverses: with current currencies, profitability increases as collective impact deteriorates; with Common Good Units, it’s the opposite. Care, sobriety, and repair become the most profitable behaviors, and the economy turns inward on itself.

Because this monetary signal, like that of our current currencies, doesn’t only affect pioneers: it propagates. It spreads through value chains. A regenerative business thus pulls its suppliers and customers towards it; an actor who chooses to preserve life draws others along, as every economic relationship becomes a shared gain for the producer, the client, the banker, the state... Care becomes contagious, circulating like the logic of profit does today, but this time sustainably, and for the benefit of all.

It is already possible for anyone interested to experience this by requesting the organization of a session of this serious game, “The Adventurers of the Common Good.” But perhaps we will also soon see the first laboratories of this experiment emerge in real life: territories where residents, institutions, and businesses agree to measure value differently and can circulate it in the form of a currency that rewards care rather than predation. This, in any case, is the project we are now working on, and the invitation we extend here to all researchers, local authorities, and companies interested in the hypothesis of an ecological and social transition that would no longer need to break liberalism and capitalism but would turn them inward on themselves—so they cease to be engines of destruction and truly become those of repair.

Money would remain magical, but not because it knows how to create wealth through destruction. Instead, because it would finally reveal what we have ceased to see: the value of a world in common.

An email based response, in French, from Lionel Grenel:

Nous avons, par le passé, déjà parler ensemble de l'UBiC et de ICGS lors d'une conversation téléphonique avec Isabelle cet été. ICGS est le nom de code, CAPS sera le nom officiel.

Je te remercie d'avoir autorisé la transmission de "Breaking the Transactional Symmetry:Towards an Asymmetric Monetary Architecture for Regenerative Economies" par Isabelle.

De mon côté, les papiers sont plus "magmatiques" (je te conseille de commencer par "Points d'entrée ICGS"):

Le papier que j'envisage de publier ("Novel Algorithmic Contributions for Economic Transaction Validation: A Hybrid DAG-NFA-Simplex Architecture with Infrastructure-First Optimization") a pour but d'intéresser de futures contributeurs

Le repository GitHub associé ("https://github.com/Norkamer/ICGS.git") a pour but de monter une 1ière utilisation concret.

De son côté "CAPS: Constraint-Adaptive Path Simplex for Economic Transaction Validation Hybrid DAG-NFA-Simplex Architecture with Algebraic Foundations and Empirical Analysis" a pour but de faire une analyse mathématique de la complexité algorithmique. Il est devenu obsolète car j'ai maintenant une meilleur approche pour la partie NFA.

Il est associé à un de mes répertoires de travail ("CAPS_EMPIRIQUE") qui n'est pas encore associé à un repository Git. J'ai pris "une tension sur les ressources hydriques avec des droits de prélèvements (circulant au niveau monétaire) avec modélisation du cycle de l'eau (entre autres, modélisation du réseaux fluvial et aquifères )" comme scénario prétexte . C'est lui qui m'a fourni l'illustration "expanded_grid_performance_summary.png" pour les performances algorithmiques.

"Multi-paradigm computational integration: The DAG NFA-Simplex research landscape" a pour but de lister tout ce qu'il y a dans la littérature académique en terme d'algorithmes associés (et j'en trouve régulièrement de nouveau).

J'ai un repository GitHub "https://github.com/Norkamer/CAPS.git" qui, en plus des éléments "core", possède un jeu que je n'utilise actuellement que comme validateur de concepts (par exemple SFC_INTEGRATION_SUMMARY.md). Si tu as un compte GitHub, c'est probablement le 1ier repository que je t'ouvrirai.

Le repository "https://github.com/Norkamer/CapsMulti.git" est construit pour faire de la vérification formelle avec des outils comme Lean4 et Isabelle (ça ne s'invente pas) et un système de calcul des crédences dans chaque affirmation. Il sera probablement la base de nouveaux papiers."

This vision sits at the intersection of what we’ve been testing and where we’re looking to go.

Over the past year, we’ve been testing a living prototype of what you describe—not through monetary reform, but through behavioural architecture.

Inside a single workplace, we built a small-scale economy grounded in reciprocal gratitude.

Time became our currency.

Trust became our infrastructure.

And value was defined by how each person’s actions aligned with their stated beliefs and the shared mission of the group.

We called it Soul Certified—a system where permission, belonging, and mattering function as currencies of the commons.

When someone acted in alignment with their truth, we reinforced it through shared recognition rather than external reward.

When someone drifted from the group’s mission, the system reflected it back without punishment—only awareness.

Thirteen people became one unified field.

Performance self-organized.

Truth became safe again.

It wasn’t perfect, but it proved something important:

when people are trusted to act from who they are—not who they think they need to be—the economy of care becomes self-sustaining.

We believe this is the psychological substrate of the Common Good economy you’re envisioning—the inner trust architecture that allows new currencies like UBiC to take root.

We’d love to explore how these two worlds—behavioural trust and economic design—could inform each other.